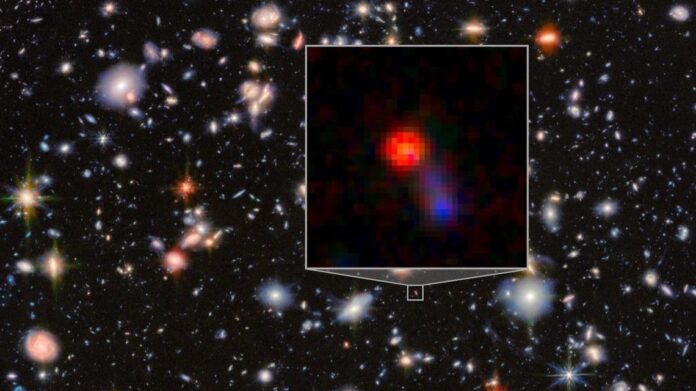

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has uncovered a supermassive black hole lurking within a distant galaxy nicknamed “Virgil.” This galaxy exhibits a striking duality: appearing as a normal star-forming system in visible light, yet transforming into a high-energy powerhouse when observed in infrared wavelengths. The discovery, published in The Astrophysical Journal on November 17th, suggests that many of the universe’s most extreme objects may remain hidden unless viewed through infrared telescopes.

The Jekyll and Hyde Galaxy

Virgil appears as it existed roughly 800 million years after the Big Bang, giving JWST a glimpse into the early universe. In optical observations, the galaxy presents itself as a young, quietly evolving system. However, JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) reveals a heavily obscured supermassive black hole at its core, emitting enormous energy. Astronomer George Rieke of the University of Arizona described this phenomenon as Virgil having “two personalities.”

“The UV and optical show its ‘good’ side… But when MIRI data are added, Virgil transforms into the host of a heavily obscured supermassive black hole.”

Little Red Dots and Early Black Hole Growth

Virgil belongs to a class of mysterious red objects known as “Little Red Dots” (LRDs), which have appeared in JWST observations of the early universe. LRDs were most common around 600 million years after the Big Bang, before sharply declining by 1.5 billion years, meaning they represent a crucial phase in galactic evolution. Their prevalence suggests a link to actively feeding supermassive black holes hidden behind thick dust clouds.

The black hole at Virgil’s center is classified as “overmassive,” meaning it’s far larger than expected for a galaxy of its size. This finding challenges conventional theories about how black holes grow.

Reversing the Order: Black Holes First?

For decades, astronomers believed that galaxies formed first, with supermassive black holes growing gradually as matter accumulated at their centers. However, JWST observations like this one suggest the opposite may be true: black holes may form before the galaxies that host them.

This discovery implies that the black holes may drive galaxy formation, rather than the other way around. As Rieke states, “JWST has shown that our ideas about how supermassive black holes formed were pretty much completely wrong.” This shift in understanding will reshape how scientists model the early universe.

The implications are profound: if black holes grow ahead of galaxies, then the fundamental structure of cosmic evolution needs to be rethought. JWST’s continued observations will be critical to resolving these mysteries and refining our understanding of the universe’s formative years.